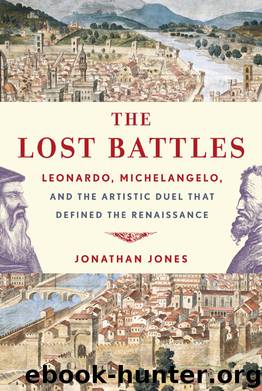

The Lost Battles by Jonathan Jones

Author:Jonathan Jones [Jones, Jonathan]

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

ISBN: 978-0-307-96101-3

Publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Published: 2012-10-23T07:00:00+00:00

This image of sacrifice as a bloody visual spectacle that rouses violent passions in the spectator is powerfully suggestive about the purpose of showing the citizens of Florence, assembled in their Great Council Hall, a savage painting of a battle. Today, in sixteenth-century Italy, says Machiavelli, the pieties of the Church honour weakness and celebrate “humility.” Christianity’s tranquillizing effect pacifies citizens and makes them easy to tyrannise. Ancient religion was the opposite: paganism valued this world and its glories, and its rites were bloody and cruel. The spectacle of sacrifice was violent and ferocious: “being terrible,” it “made men similar to itself.”

Machiavelli here advocates a use of visual horror to make citizens cruel and violent, to prepare them for war. He was ultimately concerned as a political thinker with changing the subjective feelings and dispositions, awakening the energy, of his fellow citizens. Republics in his eyes were made free by passion: people were more alive, and that means more violent, in free cities. “But in republics,” he sardonically warns would-be tyrants in The Prince, “there is greater vitality, greater hatred, more desire for revenge.” His praise of ancient blood sacrifice is on these grounds: by watching blood flow on their altars, the old pagans absorbed cruel, but strong and warlike, ways.

Leonardo da Vinci was designing a monument to fury, a painting that visually manifested the warlike passions. Armies marched to the beat of drums. What if we pictured Leonardo’s painting as the visual equivalent of a stirring drumbeat, drumming war into Florentine hearts as they met in their Hall to vote taxes to pay for the defeat of Pisa? A Machiavellian understanding might see The Battle of Anghiari as the equivalent of a pagan sacrifice, a rite of violence that, “being terrible … made men similar to itself.”

If so, it would be a true Machiavellian attack on piety. The Great Council Hall was a room drenched in religion. Built by Savonarola, it had an altar for which Filippino Lippi and then Fra Bartolommeo were contracted to paint the Virgin and the saints of Florence, a wooden loggia on top of which a nude Christ was planned. But in place of humility and sanctity, Leonardo’s wall painting would bring a vision of rage, anger, revenge—of the Machiavellian virtues. The very qualities Vasari would see in it—“rage, bitterness and revenge are perceived as much in the men as in the horses”—are, according to Machiavelli, the strengths a republic needs if it is to survive.

Fury and fire burst off the pages of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks in designs for cannons, mortars, bombs, missiles, fireships, and armoured cars. In a drawing in Manuscript B that he works up in more detail on a sheet in the British Museum, he gives form to his idea for a “covered chariot.” Leonardo’s predecessor of the modern tank is a round-roofed wagon, moved by gears, armed with cannon that blast away as it rolls across the battlefield. A note by the side of the drawing suggests some uses: “These replace the elephants.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18641)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5484)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3680)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3549)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3535)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3460)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3368)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3330)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3184)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2925)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2924)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2889)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2736)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2725)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2676)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2647)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2593)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2588)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2518)